|

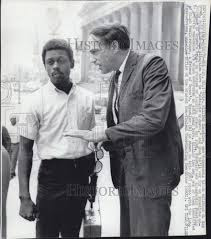

| SNCC Worker Ralph Featherstone with Attorney Bill Kunstler |

Coincidentally, less than 48 hours after Upper West Side Movement organizer and 1967-68 Columbia SDS vice-chair Ted Gold was killed, and on the same day Ted’s body was identified, a firebomb exploded in the office of the Black Panther Party’s Philadelphia chapter, at 47th and Walnut St. in Philadelphia. According to a March 8, 1970 Liberation News Service article:

“A firebomb exploded in the Black Panther Party office…early Sunday morning, March 8 [1970]. It was the fourth attack against the office in recent months.

“A bystander reported he saw smoke and flames pouring out of the first floor Panther office about 2 a.m., Sunday. He observed the plate glass window of the office was broken as if an object had been thrown through it. He called the police and fire department and went to get the residents of the upper floors out of the building. It took the police 25 minutes to arrive. The fire department made it to the scene a few minutes after the police even though the nearest firehouse is only six blocks away.

“`Someone is out to get us,’ said a Panther spokesman at the office…Two days before the firebombing, the mimeograph (chain and all), a record player and an electric heater were stolen from the office.

“The Panther spokesman said, `This is part of the national attack against the Panthers.’”

How SNCC Staff Members Ralph Featherstone and “Che” Payne Were Killed 50 Years Ago

Just 3 days after the three explosions at 18 W.11th St. in Manhattan, on March 9, 1970, SNCC staffers Ralph Featherstone and William “Che” Payne “were driving along Route 1 in Maryland when a bomb exploded beneath the floorboard of their car,” according to the SNCC digital.org website; and, as the New York Times reported, “the explosion” that killed Ralph Featherstone and “Che” Payne “occurred two miles from the courthouse where pretrial hearings were being held for Mr. Featherstone’s close friend,” former SNCC chairperson “H. Rap Brown, who” was being “charged with arson and incitement to riot” (and who, after changing his name to Jamil Al-Amin, was later sentenced to life without parole in Georgia in 2000, in a different court case, despite maintaining his innocence).

Jet Magazine published an article about the explosion, that killed the two SNCC staff members 50 years ago in Bel Air, Maryland, in its March 26, 1970 issue, which noted that “Featherstone, a long-time friend of Brown’s and reportedly a key witness in Brown’s defense, was hurled 50 feet from the car he was driving when a blast ripped through the right side of his 1964 blue and white auto;” and “Blacks in predominantly white populated Bel Air insisted that Featherstone and Payne were murdered since they were returning to Washington [D.C.] when the blast occurred.”

Police in Maryland originally claimed that the two SNCC staff members were planning to bomb the courthouse where H. Rap Brown was being tried in Bel Air or a police station there. But as the Medium.com website observed, “SNCC members and other supporters believe the two men were assassinated; killed by a car bomb placed in or on their vehicle” and “even the police” later admitted “that Featherstone and Payne were driving back to Washington at the time of the explosion, thus casting doubts on the original claim of them planning on bombing the courthouse.” In addition, a community leader from Baltimore, former Urban Coalition of Baltimore Director Walter Lively, told the Jet Magazine reporter 50 years ago that “we don’t want the police to push the idea that here were two fools, who were expert with explosives who just blew themselves up,” according to the March 26, 1970 Jet Magazine article.

An article in the March 11, 1970 issue of the New York Times also reported that the then-attorney for H. Rap Brown, antiwar and Civil Rights Movement attorney William Kunstler, “who also visited the wreckage at the state police barracks, rejected any inference that Mr. Featherstone had knowingly transported "explosives." According to the same article:

“He said he had known Featherstone for years adding `I don’t think that sort of thing was Ralph Featherstone’s bag.’ Besides, he said, Featherstone’s car was heading away from Bel Air…`Why should they be leaving town if they came here to blow something up’ Mr. Kunstler asked…”

Following Ralph Featherstone’s death, SNCC also released a statement to the press asserting that “he was murdered by the powerful forces in America that in their fear have decided to behead the Black militant movement” and “they are blaming the victim for the crime, still acting as if they can blot out ugly truth by destroying the people who speak it.”

In an article that appeared in the March 23, 1970 issue of Hard Times magazine (that was included in Harold Jacobs’ late 1970 Weatherman book), Andrew Kopkind noted that “in the months before he was blown to bits by a bomb in Bel Air, Maryland, Featherstone and several others were running a book store, a publishing house and a school in Washington” and “Featherstone and his companion, Che Payne, were most probably murdered by persons who believed that Rap Brown was in their car.” According to Kopkind, “Featherstone had gone to Bel Air on the eve of Brown’s scheduled appearance at the trial to make security arrangements” since the former SNCC chairperson “had good reason to fear for his safety in that red neck of the woods;” and “no one who knew the kind of politics Featherstone was practicing, or the mission he was on in Bel Air, or the quality of his judgment, believes that he was transporting a bomb—in the front seat of a car, leaving Bel Air, at midnight, in hostile territory with police everywhere.”

According to a March 14, 1970 Liberation News Service article, “the explosion happened two miles from the courthouse where…Rap Brown was to go on trial for having made speeches which `caused’ the 1967 rebellion of Cambridge, Maryland’s black community;” and “before Payne’s badly mangled body was identified there had been speculation that Rap might have been the second passenger in the exploded car.” The same article also noted:

“Bel Air police, worried about the reaction of Black communities in Baltimore, Washington and around the country, almost immediately put forward to the press the idea that the two young black men must have blown themselves up in an inept attempt to blow up some police station or something. Maryland’s governor Marvin Mandel put the National Guard on alert, and the prosecuting attorney in Rap’s case showed up at the site of the explosion to proclaim that the police theory seemed like a good one to him.

“`All those who have known Ralph Featherstone know that the brother would not have been carrying incendiary devices in his car’ said a close friend and fellow worker of Featherstone’s. A SNCC spokesman said, `Nobody who knows Maryland and nobody in the black community believes they were carrying that bomb themselves, but that it was planted or thrown into the car specifically for the murder of Rap Brown.

“`The people who are spreading the story that they blew themselves up are trying to build a panic, a bomb scare, to crush all public opinion against the repression that they’re building up,’ the SNCC spokesman continued. `They’re laying the groundwork for revitalizing the McCarran Act, for “Operation Dragnet” to round up all dissidents.’

“`You’d have to be a fool to ride to Rap Brown’s trial in a well known movement car knowing you’re being watched and followed, and carrying a bomb with you,’ another movement veteran remarked.

“Black movement people in Maryland are convinced that Featherstone and Williams, who were in Maryland trying to prepare a safe entry for Brown into Bel Air, were killed by KKK or John Birch Society forces, both of which are active in the area, or by some of the more official right-wingers often closely associated with them. `It is significant to note that the car that was driven and destroyed had been used over the past five years throughout the black belt of the South,’ a movement leaflet here explains. `The car was well known to state and federal authorities, Ralph and William’s presence in Bel Air was almost certainly known. A bomb must have been planted at some point during the night under the right front seat of the car.’

“Featherstone, a former SNCC National Programs Secretary, was [nearly] 31 years old at the time of his death…Che Payne was [around] 29 at the time of his death…”

But as Sue Thrasher observed in another March 14, 1970 Liberation News Service article, “the authorities in Maryland, or nationally for that matter, are not interested in finding out who is responsible for the death of Ralph Featherstone and William Payne” because “it is too easy to exploit their deaths in such a way as to make further repression even easier” and “to try to make sure that the left in this country is intimidated and destroyed.”

Time to Re-Investigate Featherstone-Payne Deaths and Fully Release FBI’s “Townhouse Papers”?

So perhaps there needs to be a new official investigation into how Ralph Featherstone and Che Payne were killed 50 years ago on a highway in Bel Air, Maryland launched in 2020? And 50 years after the deaths of former Columbia SDS vice-chair Ted Gold, Diana Oughton and Terry Robbins on W. 11th Street in Downtown Manhattan, perhaps any remaining still-restricted pages in the National Archives related to the FBI’s investigation of what happened there on March 6, 1970 should be deposited on the Upper West Side in Columbia University’s Butler Library in 2020?

(end of article)